Catastrophe in Meritah’s Great Lakes - Part III: A Holocaust

by Kasabez Maakmaah

I wish to emphasize as much as possible the desolation and emptiness of the country we passed through. That it was only very recently a well-populated country ... was very evident. After a few hours we came to a State rubber post... At one place I saw lying about in the grass surrounding the post, which is built on the site of several very large towns, human bones, skulls, and, in some places, complete skeletons. On inquiring the reason for this unusual sight : ‘Oh!’ said my informant,’When the bambote (soldiers) were sent to make us cut rubber there were so many killed we got tired of burying, and sometimes when we wanted to bury we were not allowed to.’

‘But why did they kill you so?’

‘Oh! Sometimes we were ordered to go, and the sentry would find us preparing food to eat while in the forest, and he would shoot two or three to hurry us along. Sometimes we would try and do a little work on our plantations, so that when the harvest time came we should have something to eat, and the sentry would shoot some of us to teach us that our business was not to plant but to get rubber. Sometimes we were driven off to live for a fortnight in the forest without any food, and without anything to make a fire with, and many died of cold and hunger. Sometimes the quantity brought was not sufficient, and then several would be killed to frighten us to bring more. Some tried to run away, and died of hunger and privation in the forest in trying to avoid the State posts.’

‘But,’ said I, ‘ if the sentries killed you like that, what was the use? You could not bring more rubber, when there were fewer people.’

‘Oh! As to that, we do not understand it. These are the facts.’ ...

And looking around on the scene of desolation, on the untended farms and neglected palms, one could not but believe that in the main the story was true. From State sentries came confirmation and particulars even more horrifying...all combined to convince me over and over again that, during the last seven years, this ‘ domaine privé ‘ of King Leopold has been a veritable ‘hell on earth.’

From the Roger Casement Report, 1903.

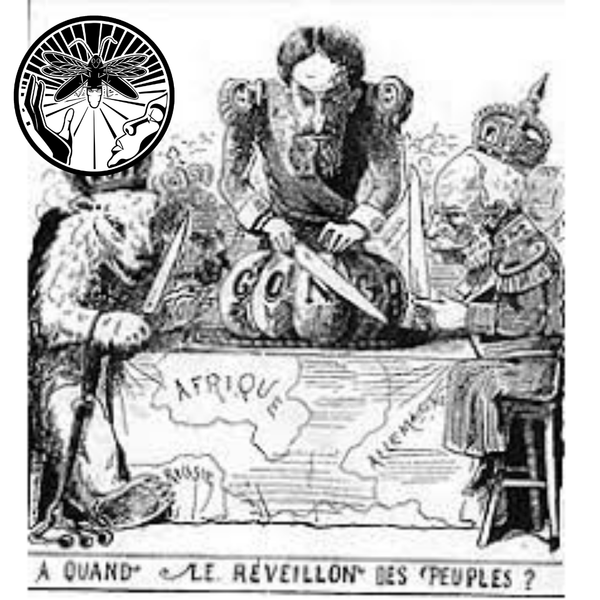

At the Berlin Conference in 1885, The leaders of several European nations with colonies in Meritah (Africa) met to discuss their strategy for colonising the continent without fighting each other in the process. During these negotiations, they determined which countries would have “rights” to claim certain territories. King Leopold II of Belgium secured for himself a vast region surrounding most of the Congo River to rule as his personal property. He called this territory the Congo Free State. It was called a “free state” because rules of free trade were to apply and corporations were free to come there to claim land to exploit for their profit. From the time of the Berlin Conference until 1908, an estimated 10 million “excess” deaths occurred in this region alone, meaning under normal circumstances there will be a certain number of deaths naturally and that during this period, there were about 10 million more than normal.

Following the conference, Germany also sought to rapidly expand its colonial empire. German East Africa was established in the region that now comprises the present day countries Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi and part of present day Mozambique. German East Africa stretched from the east coast of Meritah inland to the Great Lakes Region. It bordered the Congo Free State and Uganda at its northwest corner. Two traditional kingdoms existed within the borders of the northwest region of German East Africa, Ruanda and Urundi (now Rwanda and Burundi).

As we will see, the 30 years between the Berlin Conference and years following World War I dealt a devastating blow, not only to the people of the Great Lakes region, but the entire continent of Meritah. The events taking place were on too large of a scale to be seen only as a local issue but here we will focus on strategies and effects of colonisation in some local examples which reveal, on some level, the global strategies and effects of colonisation.

The invasion and colonization of Congo began long before the Berlin conference. The Portuguese made contact with the Kongo Empire in 1483. Several Kongo nobles were taken to Portugal and returned 2 years later. At this point, the King of Kongo, Nzinga a Nkuwu converted to Catholicism. In 1491, Nzinga a Nkuwu and his principal nobles were baptised and the king adopted the Portuguese name, Joao I after the Portuguese King at the time, Joao II. That same year, a Kongo citizen returning from Portugal opened the first colonial school, all one year before Columbus made his historic voyage to Maanu (the Americas).

As usual, the introduction of Catholicism was immediately followed by the institution of the slave trade in the region. Nzinga a Nkuwu’s son and successor, Mvemba a Nzinga, recognised the devastation of the slave trade even in its early stages. However, he may have been too naive to realise that by accepting European religion and education, he was opening the door for Portuguese exploitation. His complaints to the Portuguese court were made in vain. This trade would lead to systematic raids inland, up the Congo River for the next 400 years. The consequences were devastating, not only because of the depopulation of the region but also due to the degradation of the culture. Material goods brought by the portuguese became the reason for violating the bonds of trust and brotherhood which existed there for thousands of years.

At the Berlin Conference, King Leopold proposed a humanitarian mission to end slavery and civilise the “savages” of the Congo Region. As usual, “humanitarianism” was the justification for these governments to claim ownership of lands inhabited by other people. This was simply the beginning of the next phase of colonisation taking root in the region, which was vulnerable following the era of the slave trade.

In order to legitimise their claims to ownership, agents of these governments supposedly met with local chiefs to sign treaties. These treaties effectively gave legal possession of the land to Europeans. In the case of the Congo, the agent of King Leopold was Henry Morton Stanley. In the case of German East Africa, Carl Peters, who was inspired by Stanley’s writings, began colonisation for Germany. The contracts were really a formality that meant that other European countries could not claim those same lands. In Meritah, where the European law of contract was not recognised, control of the population would have to be achieved by any means necessary.

The Destruction of Congo

“The progress of the native in civilization will not be secured until he has been convinced of the necessity and the dignity of labour. Therefore, I think that anything we reasonably can do to induce the native to labour is a desirable thing.”

Joseph Chamberlain, British Colonial Secretary, 1901

“It is generally admitted that the native has no real title to the ownership of the vast stretches of country which from time immemorial he has allowed to lie fallow, or to the forests which he has never turned to profit.”

Official Bulletin of the Congo Free State, June 1903.

The above statements reflected the attitudes of the colonial leaders of that era, or at least the excuses they made to justify their greed and barbarism. This is consistent with the propaganda that continues to this day which present’s Meritah as a continent in need. In every case, the same countries presenting themselves as benefactors only have one agenda, to continue to rob and exploit the people and land. The above quotes were made in response to a report by Roger Casement. Following these rebuttals, Casement launched a more thorough investigation into the atrocities being committed and documented extensively the reports given to him by the Meritahwi he encountered. Published in Britain in 1904, this “Casement Report” brought about widespread public outrage and brought disgrace to both Leopold II and Stanley.

Casement’s report was based on an investigation he conducted in 1903. According to his first hand account, it had become the duty of the many tribes who had been forced to share the Congolese national identity to provide anything the corporate government required for its operation. Every village or town Casement encountered had been effectively reduced to a slave camp whose populations were forced to provide goods and services to corporate authorities, including food, lumber, and labor for any task. The major product being demanded for export to Europe was rubber which was extracted from certain vines that grew in Congolese forests. This rubber was required for tires for automobiles which were becoming more accessible due to these “humanitarian” efforts in the Congo and elsewhere. European corporations often controlled these forests and forced the local populations into slavery. Of the villages in the forests surrounding Lake Tumba, Casement reported,

“During the period 1893-1901 the Congo State commenced the system of compelling the natives to collect rubber, and insisted that the inhabitants of the district should not go out of it to sell their produce to traders. The population of the country then was not large, but there were numerous villages with an active people—very many children, healthy looking and playful. They had good huts, large plantations of plantains and manioc, and they were evidently rich, for their women were nearly all ornamented with brass anklets, bracelets, and neck rings, and other ornaments.”

Casement listed population estimates of several villages surrounding the lake from 1893 to 1903. The total estimated population of those villages went from 12,320 in 1893 to 1,610 in 1903. Casement added,

This list can be extended to double this number of villages, and in every case there has been a great decrease in the population. There are more people in the district near the villages mentioned, but they are hidden away in the bush like hunted animals, with only a few branches thrown together for shelter, for they have no trust that the present quiet state of things will continue, and they have no heart to build houses or make good gardens.

While the legacies of Leopold II and Henry Morton Stanley were tarnished by the public exposure of their brutality in building the Congo Free State, the examples of colonisation described above were typical of tactics used throughout the world. Soon after the Casement Report was published, a major uprising known as the Maji Maji rebellion began in German East Africa. In 1905, apparently in response to new cotton plantations that were implemented in the region, the uprising began and spread across more than 1/3 of the colony. At the time, there were only a few hundred German soldiers with the help of a few thousand African soldiers (known as askaris) in the entire territory attempting to control hundreds of thousands of people. Since they were so badly outnumbered, they turned to a tactic called “slash and burn” meaning they went across the country burning crops with the goal of causing a famine. A German Captain wrote to his commander, “Only hunger and want can bring about a final submission. Military actions alone will remain more or less a drop in the ocean.”

Uprisings of this nature were commonplace throughout the continent during this period and the European response was consistently savage. The colonists usually succeeded in finding Africans who were willing to act as the hand of the oppressor, convinced that they would still be better off than the oppressed. This tactic of divide and conquer has been successful everywhere in the world and is still employed today.

Disease Epidemics

The brutality of the colonists led to conditions amongst the Meritahwi that invited sickness. Massive population declines were not only the result of mass murder, but also disease epidemics which had previously been unknown. These epidemics ravaged the populations in the Congo in particular, where it’s estimated that fully half of the population along the lower Congo River died from smallpox and a disease called sleeping sickness alone. Sleeping sickness was considered a death sentence as almost all reported cases resulted in death. This illness reportedly spread via the supply lines of the Congo State. This epidemic spread outside of Congo River region to the Great Lakes Region, killing at least another 250,000 in Uganda from 1900 until about 1905 and thousands more throughout the region. Populations throughout the Great Lakes region were also decimated by Smallpox in 1892. While smallpox likely arrived with the invaders as it had in Maanu (the Americas), the origins of sleeping sickness and the reason for its spread are hard to pinpoint. The timing of the epidemic with this period of colonisation should not be overlooked. Regardless of the reason for the outbreak, we see that the colonists took full advantage of the weakened state of the native populations.

The Great War

In 1914, this ongoing catastrophe would take a turn for the worse. During World War I, German armies would fight the armies of Britain, Belgium and Portugal in Meritah. It’s even speculated that conflicts amongst the European nations over their colonies in Meritah was a major reason for the start of this war. Though this was a war between European countries, the majority of soldiers on either side of the war in Meritah were the Askaris. In addition to the soldiers, countless men were forced to serve as carriers, literally carrying supplies for the armies across the continent. The British army alone conscripted about a million men for this purpose. They estimated that by the end of the war in 1918, about 200,000 of them had died during the war.

This widespread, forced recruitment of soldiers and carriers for these armies created another huge problem. Men were forced far away from their homes and were unable to care for their farms. Communities across the continent were forced to feed these armies. In many cases, armies destroyed farms in order to starve their opponents, but the innocent victims were the families which were already forced to survive without the presence of their most able men. Following a drought in 1917, severe famine swept the continent. Normally, food is stored for times of famine, however this was impossible under these conditions. As a result, tens of thousands starved to death in German East Africa alone. Although devastating, the worst was yet to come.

Fighting in Meritah would continue until about 2 weeks after the war in Europe ended. Right before the armistice (ceasefire) on November 11, 1918 a deadly pandemic flu virus in Europe spread worldwide. This virus, known as the “Spanish Flu” killed an estimated 50-100 million people worldwide, approximately 3-5% of the human population at the time. This virus, either through simple negligence or malicious conspiracy, was spread to Meritah and the US from England in August of 1918. This virus decimated the surviving Meritahwi already fighting to survive the aftermath of the war, famine, disease and enslavement by the Europeans. It’s estimated up to 2,000,000 Meritahwi from south of the Sahara died from the pandemic alone.

It’s difficult to attempt to measure the suffering and death in Meritah during the war. At a certain level, the numbers start to lose their meaning. Looking at the big picture, what was really happening may have been the sledgehammer that broke the camel’s back for so many people and cultures of Meritah. While fighting for the same countries that were colonizing them, the Meritahwi were unaware that they were being played like pieces on the chessboard. While thinking that they will be better off if they support the winning side, they were unaware that the invaders’ plan all along had been to get them to fight each other until they were defenceless.

Prior to the war, frequent resistance movements in response to rampant European savagery and terrorism led to the constant need for military interventions by the colonists. European investors and politicians were concerned that colonization in Meritah was costing as much as the value of the products coming from the colonies. The devastation in Meritah after World War I provided the European leaders the opportunity to continue their conquest of the continent with less resistance. The next phase in their conquest would be shaping the minds of Meritahwi to ensure that they would see their oppressors as their only salvation.

Imagine a civilisation trying to regroup from the horrors that colonisation brought from the Berlin Conference in 1885 until the end of the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1919. Imagine the disruption of knowledge being passed from generation to generation because it had become so difficult to simply survive. Imagine at the same time, the colonists plotting how they will educate those orphaned during the war to serve their agenda or how they will control the trade routes, resource extraction and food production in those regions where millions of men have been displaced and were unable to protect their families and villages. This is the “civilisation” that the humanitarian efforts of Europe brought to Meritah. As we shall see in part four, the catastrophe has continued for almost 100 years since.